| |||||||

| |||||||

|

|

1972 - Speedway Ruined My Toffee Apple

Previous chapters: 1970 ; 1971

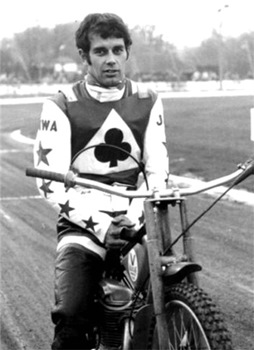

Belle Vue were straight into to the league action the next season with a home match against Wimbledon. The Dons were led by former World Champion Ronnie Moore, who had won the title twice in the 1950s. He was one of the few riders who were still around from the time my Dad first went to watch speedway. Wimbledon had the second most iconic team colours of any British speedway track, a yellow star on a red background. Of course these colours couldn't have been as iconic as the black ace of clubs on the white triangle centred on a red background, the colours of the Belle Vue Aces. By now I had my own programme board in Aces colours. A programme board is an essential piece of equipment for the dedicated speedway supporter as filling in the scores is vital to following the match. I'd seen people with bits of wood painted in the Aces colours, and I wanted one the same. We found in the garage some pieces of plywood that made up record shelves in Dad's old desk which were the perfect size. They even had a curved bit cut out that meant it fitted nicely against your tummy. Mum painted it up in red with the white triangle and the black aces of clubs on one side, and some blackboard paint on the other. Dad brought home a big bulldog clip from the office and it was complete. It also served a useful secondary purpose as a shield when the riders came past. If you held it at the right angle you could still watch the race whilst avoiding having your face pebble-dashed with granite or shale (depending on the track you were watching at). I never really understood why Belle Vue used granite in those days. Halifax's track was black as well, although everywhere else we went used the red shale that most people would be familiar with. The red always looked better to me, and the only track where I've seen the granite used in recent years is at Buxton. When the track was wet the racing would be awful. Matches went ahead in those days on tracks that would never be raced on now. Belle Vue's home match with Exeter that season was one such. Every race was in the region of eighty seconds long, and Exeter must have forgotten their wellies as they succumbed 59-19. Although this wasn't quite as big a score as the defeat of Oxford the previous year, the last nine heats finished 5-1 to the Aces. Riders often wore mechanics' overalls over their leathers when it was wet so they wouldn't have to clean as much muck off after the meeting. At speed the wind would inflate the overalls giving an impression of the Michelin man a motorcycle. If there was one rider that regularly had the beating of Ivan Mauger it was Ole Olsen. Ole had beaten Ivan to take his first World Championship in Gothenburg the previous September. Although you expected Ivan to beat everyone else, it had now got to the stage that you expected Ole to beat Ivan. Belle Vue hosted Wolverhampton in a challenge match that May, and as number ones Mauger and Olsen were due to meet in the first heat. In a bit of an anti-climax Ivan dropped out of the race and Ole won easily. In fact Ivan didn't finish in his second race either so something was clearly wrong. Ole Olsen was looking forward to riding unbeaten all night. That was until he came up against Peter Collins in the final heat. PC and Soren Sjosten were up against Olsen and former Aces rider Dave Hemus, who had moved to the Wolves in the winter. In an absolutely breathtaking ride Peter Collins passed the World Champion to win. The stadium erupted and my heart was beating so loudly I didn't hear the race time announced. Since first seeing him in the opening meeting of 1971 everyone saw the potential in Peter Collins to be a world beater. Now that potential was becoming a reality. People who don't get speedway think that the first rider away from the start always wins. Try to tell them that's not always the case and they'll say if speedway wasn't so predictable you wouldn't try to prove it wasn't. You can't win. In any form of motorsport being first away from the start is important. Someone once said about motor racing that time lost at the start is never made up. Ivan Mauger was such a successful speedway rider because he was determined to be the first man into the first corner, and most times he was. He was so quick and consistent that once in front he was very unlikely to be passed. That wasn't because speedway was boring. It was because Ivan Mauger was the best. To a certain extent Peter Collins was the opposite. If Peter ever made the start it was as surprising as if Ivan didn't. In Peter's case time lost at the start could be made up by finding the line or the grip that other riders weren't using. He would often ride a line that people now call a diamond, by riding deep and wide into the turn before cutting back and passing on the inside. If he couldn't pass on the inside he'd pass on the outside, and if needs be he'd pass on the straight. Speedway is motorcycle racing on a loose and often wet surface. Traction is everything, and PC, even at age seventeen, had the ability and technique to find grip when more experienced riders couldn't. The World Championship Qualifying Round at Belle Vue that year was won by Ivan Mauger with a maximum, Chris Pusey second, and Jimmy Mac came back from Glasgow to finish third. It was a shorter World Championship qualifying process for the British and Commonwealth riders that season. The World Final was to be held at Wembley in what was now a three year cycle with Poland and Sweden. Riders would race in three WCQRs, one at their home track and two more at other tracks. The top thirty-two would be divided into two semi-finals with the top eight from each racing in the British Final at Coventry. The top five from this meeting would qualify directly for the World Final where they would meet eleven others who had taken the European qualifying route. In earlier years the World Championship Qualifying rounds qualified the top sixteen scorers for the final, which was always at Wembley, in an age when the speedway World really meant Great Britain. The route to the final had changed, but the initial rounds hung onto their name. New Zealander Ivan Mauger would win the British Final. Speedway at Belle Vue took on an international flavour in mid-June when the Leningrad Neva team came to town. The Aces had taken on the team from the Soviet Union two years earlier, but I had missed it. Non-Russian Ivan Mauger wasn't in the Belle Vue team that night, but the Leningrad team was well sprinkled with Viktors, Anatolis and Vladimirs to make up for it. The match was much closer than I expected as some of the Russian boys were really quick, and clearly liked the big Belle Vue track. It's highly likely they had the best Jawa equipment that the state-sponsored rouble could requisition, but then all was fair in love and cold war era speedway. Belle Vue won 41-37, but it showed that the Russians knew how to race. The following Saturday Belle Vue were home to the newly promoted Ipswich with their star rider John Louis, who was impressing at the higher level, and would qualify for the World Final. The Harwood family were, however, camping in Yorkshire that weekend testing out our new tent, so took in the Halifax v Wimbledon match at the Shay. A young Swedish rider making an impression with his speed that season was Tommy Jansson. Apparently very good looking, he was making another sort of impression with the lady fans. I was more impressed with his riding ability, and noted his three straight wins after a first race EF. Oxford at home were up next, and although not as awful as in the previous season still suffered a 55-22 spanking. They weren't helped by the fact that for the third year running on a visit to Hyde Road, Norman Strachan failed to score a point. Another habit continued next match when I once more failed to see Barry Briggs ride in a league match for Swindon. Ivan wasn't riding either as he'd done something very rare. Not only had he fallen off, but he'd broken bones in both wrists. Not the worst injuries ever but very inconvenient for a speedway rider needing to use clutch and throttle and contend with the vibrations of a rigid-framed speedway bike. We had to hope he'd have recovered by the time the World Final came round. Ipswich's John Louis proved a useful guest rider winning two of his four rides, and was to reappear at Belle Vue a few weeks later guesting for Poole. Ivan's wrist injuries were proving manageable with strapping and painkilling injections, and he was able to warm up for the World Final with a leisurely maximum against Newport, who proved as easy to turn over as ever as the Aces won 56-22. 16th September 1972 was World Final night. The World Speedway Championship Final at Wembley, sponsored by the Sunday Mirror, official programme 20p. Accommodation for the night was the Camping Club of Great Britain camp site at Denham in Buckinghamshire, leaving us only a short drive to Wembley. The camp site wasn't full but everyone who was there was there for Wembley. We were a camping family. We had a big frame tent with sleeping compartments for Mum, Dad and Helen, and I had by own little blue ridge tent which we would set up alongside. Camping holidays in France made it almost impossible to keep up with the speedway results. If a two day old Daily Mirror could be found you might find some results tucked away inside the back pages, but more often than not it was a case of falling upon two weeks worth of Speedway Star and News the minute the front door was unlocked. The drive to Wembley took us past the headquarters of London Weekend Television, the people that brought us World of Sport on a Saturday afternoon. I was excited that I would be able to watch highlights of that night's final on TV. Not as excited as my sister was when a gold Mercedes-Benz with Swedish number plates pulled up alongside us at the traffic lights. Sitting in the back seat was a teenage boy with collar-length dark curly hair. He was the best looking boy I had ever seen, although the age of twelve I wouldn't have admitted that to anyone. "That's Tommy Jansson," I said. We had to lock the car doors to keep Helen from getting out of the Cortina and climbing into the Mercedes. If the Empire Stadium, Wembley had car parks we didn't see them. We parked in a side road of council houses about twenty minutes walk away. Forty years ago residential areas weren't full of cars and parking was easy, and safe. Car locks were just a waved gesture at security, but you never expected your car to be broken into or find a window smashed when you came back to it. The short walk took us past Freddie Williams's garage. "World Speedway Champion 1950 & 1953" the sign over the big double doors announced. I already knew that Freddie Williams had been World Champion, and I knew he was Welsh and I knew he rode for Wembley. In fact by then I knew the names of all the World Champions from Lionel Van Praag in 1936 all the way to Ole Olsen in 1971. I could tell you there was no World Final in 1939 due to the outbreak of war, and that Tommy Price was World Champion in 1949 when the World Speedway Championship resumed. I knew all this because of Speedway '70, a Gresham publication compiled by Donald Allen. One week there was no Speedway Star and News on the Oxford Road station branch of John Menzies, and Dad had picked up the only other magazine there with the word "Speedway" on the top. Speedway '70 was basically a speedway annual that had come out in the middle of the 1970 season. It was a collection of articles about the boom in speedway in the UK, and the growth of the sport around the world. It contained the obligatory photographs of Ivan Mauger and Barry Briggs, plus an agreeable number of pictures of Belle Vue riders such as Chris Pusey and Tommy Roper. It had the most wonderful colour photographs of speedway racing taken at mainly London tracks like Wimbledon, Hackney and West Ham with the bright team colours burning through the page against a background of black leathers and red shale. Near the back there was a two page spread showing the lists of scorers in every World Championship final ever. I would just stare at these pages, absorbing every statistic. Who won and when, who they rode for, where they came from, where they finished, and whether they were still riding now. Peter Craven of England and Belle Vue had won in 1955 and 1962. Barry Briggs of New Zealand and Wimbledon, and later Southampton and Swindon, was certainly still riding and had won in 1957, 1958, 1964 and 1966. The Belle Vue team manager Dent Oliver of England had ridden in the 1949 final and finished last on no points. Jack Biggs of Australia and Harringay, who so nearly won in 1951 was still riding for Hackney in 1970. Within days I could name the top three finishers in each final, and regularly tested myself to stay on top of my game. This secret knowledge served no purposed other than to satisfy me that I knew about speedway. The rider with the most world titles to his name was Ove Fundin of Sweden, but he had now retired. Next came Barry Briggs with his four, and Ivan Mauger had won his "triple crown" of titles between 1968 and 1970. In the build up to the final the talk was of whether Ivan could equal Barry's four titles, or Barry would equal Ove's five. This probably was thirty-seven year-old Barry's Last Remaining Chance. Wembley stadium on the outside took me by surprise a little. Plaster work was crumbling away to reveal the blocks underneath, and growth was sprouting out between cracks in the masonry. Just as Belle Vue stadium was a relic of an earlier time, so was the Empire Stadium. The queue for programmes was long but moved quickly. 20p for a programme was a lot. Programmes at Belle Vue were only 6p. Still this was the World Championship Final. The artwork on the cover depicted a silhouette of a rider in black leathers with a blue map of the world on his chest. I recognized the figure as being Martin Ashby of Swindon. "What's he doing on the cover", I thought, "he's not even in it." World Final night was a time for everyone in speedway to get together and I noticed Newport's Neil Street, who would later be Jason Crump's grandfather, chatting on one of the staircases. One person I didn't expect to be there joined the programme queue behind me. I turned round when I heard a voice I recognized from the telly. It was West Ham footballer Trevor Brooking. It was quite a climb up the steps once inside. Our seats were to be in the upper level overlooking the entry to the first turn. If I'd been less than impressed with Wembley Stadium on the outside, then Wembley Stadium on the inside took my breath away. Up to then the biggest crowd I'd ever seen was the reported 25,000 at Belle Vue for the BLRC. Depending on what you read the crowd this night was between 75,000 and 90,000. The British Speedway Promoters Association never published accurate attendance figures, nor did individual promoters announce attendances at their own tracks. For bookkeeping reasons crowd numbers were probably kept private. Every seat was filled so if there were any gaps it must have been in the standing areas at each end. We looked down on the parallel ribbons of red shale speedway track and golden greyhound track. Wembley's famous football turf was taken up at each side of the pitch to reveal the part-time track. Only the bends at Wembley were permanent, and I loved seeing the footballers on TV march out over the speedway track before the FA Cup final from the tunnel that doubled up as the speedway pits. Flash bulbs from thousands of Kodak Instamatics popped away and flags waved. Opposite I could see Danish flags waving for Ole Olsen, but whether these were being waved by Danish fans or Wolverhampton fans I couldn't tell. British speedway fans' national allegiances tended to side with the country your top rider came from, not necessarily where you were born yourself. Looking down into this huge bowl of a stadium full of colour and noise was making my heart beat faster. I was probably sitting further away from the track than I had before but the view was exceptional. I wouldn't miss a thing. It took four attempts to get the first heat away, only adding to the tension. Eric Boocock and Anders Michanek both fell in separate incidents, and were excluded. The final rerun was an easten bloc whitewash as Pawel Walosek of Poland and Grigory Chlinovskij of the Soviet Union were the only finishers. What might have been the biggest shock of the night, if the meeting had ended after heat two, came next. Ivan Mauger, riding with strapped up wrists and painkilling injections due to his broken scaphoids, was doing his customary gardening with the other three patiently lined up alongside. The referee Georg Transpurger released the tapes as Ivan was still rolling backwards, and Barry Briggs took a lead going into the first turn that he was never going to lose. We were in stunned. No one had expected that. Despite the advantage he was given at the start Briggo looked sharp, and very determined. Maybe this would be his night after all. Another surprise of the night was Ivan Mauger's black leathers. Much was made in the press following the World Final of Ivan's decision to wear black when we were much more accustomed to seeing him in trendy coloured leathers. By 1972 the almost universal wearing of black leathers had been replaced by coloured ones, mostly plain colours with a stripe here or there, and in the case of Ivan and Briggo a Jawa logo on each shoulder highlighting their close ties with the Czech manufacturer. Ivan's thinking was that in tight situation his opponents might pay less regard to a rival in black than the more recognizable multi-coloured suit he usually wore. In fact they might even think he was a Russian, he was quoted as saying. The fact that these were the same black leathers he'd worn to win the title at Wembley three years earlier was completely overlooked. In the next heat England's big hope Nigel Boocock was up against three Russians, and lost out to Anatoli Kuzmin, who had impressed on his visit to Belle Vue with Leningrad earlier that year. Using Ivan's theory Nigel's bright blue leathers might have been a hindrance. Heat four was Ole Olsen's first race of the night. The reigning champion was up against two Swedes, the uncompromising Bernt Persson of Cradley Heath, and Christer Lofqvist of Poole. The fourth rider in the race was England's John Louis who had caused a shock by qualifying for the World Final in only his first season as a Division One rider following Ipswich's promotion the previous year. At the start Olsen was left badly, and Lofqvist shot into the lead. Ole made up ground by passing Louis and Persson, but as he attempted to go round Lofqvist entering the first turn beneath us, he overslid and dropped his bike against the fence. A mixture of gasps and cheers went up around the huge stadium. I managed both. I didn't want Ole to win, but for the World Champion to lose by falling seemed an unnecessary humiliation. As events would turn out it was an overtaking attempt he didn't need to make. After one ride each the two biggest hitters taken a heavy blow to their chances. The next race would show us whether Barry Briggs really was a contender. Wearing the number thirteen race jacket meant that Bernt Persson was having his second ride on the run, and would be starting on the inside gate. Briggo in white was on gate three. Either side of him were the Russians Chlinovskij and Gordeyev. As in heat two Briggs was away first and got to the white line squeezing Persson out, but halfway through the turn he seemed to lose speed and drift half a yard wide. Persson drove into the gap and as the two men touched Briggs fell, only to have Valery Gordeyev ride straight over him launching his bike onto the greyhound track. I don't remember the booing for Bernt Persson, and I don't recall him being the cause of the crash, although many (including Barry Briggs) are of that opinion. YouTube is a useful tool for filling in the gaps in forty year memory, but I'm not going to use it to give an opinion I didn't have at the time. The fact was that Barry Briggs was sitting in the middle of the track holding his hand. Although a spectacular crash, it couldn't have been that bad because he was sitting up. Mum was distressed as there always seemed to be someone having a bad fall whenever she came to speedway with us. Trying to explain that bad falls happen all the time didn't help much. Speedway riders risk serious injury every time they go out to race, and it's the screamers they seem to get up and walk away from. It's the sly little slides into the fence that are the nasty ones, as happened to Dave Hemus at Belle Vue the previous season when he broke a bone in his back. Surely Briggo would be back in the rerun as there was no white exclusion light showing. As we waited it became apparent that this was bad. We didn't know until later that Barry Briggs's first and second fingers on his left hand were almost severed and he would ultimately have the index finger amputated. As he fell his hand had been caught in the rear wheel of Grigory Chlinovskij's bike, and his soft leather glove had given little protection against the spinning spokes. Persson won the rerun almost unopposed in the fastest time of the night. Real racers retain their focus whatever happens, and despite the accident that had befallen his friend and compatriot, and with a potential threat now removed, Ivan Mauger took the next race for his first win of the night. Ole Olsen got his first points with a steady win over Anders Michanek in heat eight before having to face Ivan Mauger in heat nine. As so often seemed to happen, Ole beat Ivan, although not without having to come from the back, as the Russian Kuzmin headed them both at the start. In three races Ivan Mauger had already dropped two points, but more crucially, Ole Olsen had dropped three. The riders who seemed to be making most capital from the favourites losing their way were the Swedes Persson and Lofqvist, who after three rides each were now sitting on eight points. Ivan Mauger, Ole Olsen and Bernt Persson all won their fourth races, but Lofqvist slipped out of contention when he could only trail home last in his race with Mauger. He would win his final race and finish on eleven points on a night of "might have beens". In heat nineteen Ivan Mauger was up against Bernt Persson. Ivan had to win. If Persson could finish second or better, with Ivan behind him, then the Swede would be World Champion. As it turned out Ivan made no mistake and stayed in front for four laps. There would now need to be a run-off to decide the 1972 World Speedway Championship. I don't know how Bernt Persson felt but I was almost sick with nerves. Ivan Mauger seemed to have his nerves totally under control, but whenever didn't he? He slowly rode a lap of the track before lining up for the start, and then made the gate. Despite a last lap attack by Persson, Ivan Mauger took his fourth world title. Returning to the pits gate he received the traditional "bumps" from fellow riders, including Ole Olsen who could reflect at leisure that if he'd settled for second place in that first ride he might now be World Champion for a second time. However it was a happy Belle Vue and Ivan Mauger supporting Harwood family that headed back to Denham for the night. We would see more Mauger v Olsen rivalry before the season was out. Only a fortnight later at Hyde Road Ivan beat Ole in the first heat of Belle Vue's league match against Wolverhampton, only to lose to him in the Golden Helmet match race after the interval. In the British League Rider's Championship the following month Olsen would win with an impeccable maximum as Mauger was plagued with bike trouble, although I couldn't help feeling that Ivan wasn't quite showing his normal level of determination by the end of the meeting. In his heat sixteen race with Ole I noted "Ret" against his name, rather than the "EF" I'd written after his previous heat. On 25th October the Belle Vue Aces completed a league and cup double by beating Hackney 82-73 on aggregate in the Knock Out Cup final. In the 1972 season Belle Vue had won all but three of their league matches. Every match at home was won, and away there were only defeats at Wimbledon and Reading, and a draw at Halifax. Their dominance of the British League was so great that before the following season started they would be forced by the Speedway Control Board to give up one of their top riders. Adamant that he would not lose any of his home grown talent, team manager Dent Oliver reluctantly released Ivan Mauger to Exeter. In my first three years of watching speedway, my team had won the league title every season. They had won the Knock-Out Cup, and supplied the World Champion twice, one time of which I had witnessed. I had truly been spoiled. The following season would be much tougher.

This article was first published on 1st December 2013

"Reading this reminded me of every meeting I attended as a youngster, although I started watching Newcastle Diamonds in 1975 and my 1st world final was 1978. I look forward to your next chapter." "An excellent look back at the late 60's / early 70's. I was a West Ham fan then, and ultimately Hackney, but did lots of away trips with the Hawks, the Belle Vue one being of prime importance. What great days, never to be relived sadly, but happy memories nonetheless." "Oh man, I'm lovin this !!!" "I do enjoy these articles, however I do find the constant jibes about Norman Strachan a little distasteful. Norman came to my club Newport in 1968, although never a world beater was a solid 6 point second string . However in 1969 he was averaging over 8 a match and riding the best speedway of his career. Until a match with Sheffield when Arnold Haley clashed with him at Newport, a really nasty crash. Norman was out for a while but when he came back sadly was never quite the same and maybe went on racing longer than he should have, in my view Haley left a legacy on Norman. So I would ask the writer not to be so damning of Norman when he never seen him at his best on another track." "Great article - brought back lots of memories, as '72 was the year I started getting into speedway more seriously." "Please can I assure Martin Wilkins that I bear Norman Strachan no malice whatsoever. These are my reflections on my memories from being a child. I have nothing but admiration for anyone that hurls themselves sideways round a speedway track on a motorcycle with no brakes."

|

||||||

| Please leave your comments on this article (email address will not be published) | |||||||